Marylin and The Goats

Subtitle: Mathematicians fooled by probability, an R experiment to show why they're wrong

Controversial Ask Marylin column about the Monty Hall problem solved.

Throw out your gold teeth and see how they roll;

The answer they reveal: life is unreal.— Your Gold Teeth II, by Steely Dan

# Marylin

Marylin is very smart, maybe the smartest person in the world. She has written short stories, magazine and newspaper articles, and more than 20 books. She became financially independent by investing in stocks and real estate, and in 1985 was listed in The Guinness Book of World Records as the person with the highest IQ in the world with an IQ of 228. She took her mother’s name, vos Savant as her last name, and on August 23, 1987, she married Robert Jarvik, who developed the Jarvik-7 artificial heart. She is also a descendent of the physicist Ernst Mach, sometimes going by Marylin Mach vos Savant.

"To acquire knowledge, one must study; but to acquire wisdom, one must observe."

—Marylin vos Savant

In 1986, Parade Magazine published a profile of her, and it was so popular that they asked her to write a weekly column, Ask Marylin. The IQ test that made her famous was written by philosopher Ronald K. Hoeflin, called the Mega Test designed to find people with one in a million IQs (99.9999th percentile), which admits them to the Mega Society. The test was first published in the April 1985 issue of OMNI magazine, and a high score would also admit you into less intelligent groups such as the Triple Nine Society (99.9%), The International Society of Philosophical Enquiry (99.96%), The Prometheus Society (99.99%), and the Titan Society (99.999%). Pity the poor Mensans with IQs merely in the top 98th percentile.

# The Goats

In 1990 a reader of the Ask Marylin column wrote, “Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”

In 1975 Steve Selvin, a statistician at UC Berkeley, presented the same problem to the American Statistician, calling it The Monty Hall Problem from the game show Let’s Make a Deal.

Monty Hall is required by the game rules to

- always open a door that was not picked by the contestant

- always open a door to reveal a goat and never the car

- always offer the chance to switch between the originally chosen door and the remaining closed door.

Should you stick with your original choice of Door #1, or switch to Door #2?

In her column, Marylin said that you should always switch doors. Then the letters poured in 10,000 of them and 1,000 of those from Ph.D. statisticians and mathematicians.

You blew it, and you blew it big! Since you seem to have difficulty grasping the basic principle at work here, I’ll explain. After the host reveals a goat, you now have a one-in-two chance of being correct. Whether you change your selection or not, the odds are the same. There is enough mathematical illiteracy in this country, and we don’t need the world’s highest IQ propagating more. Shame!

—Scott Smith, Ph.D., University of Florida

I am sure you will receive many letters on this topic from high school and college students. Perhaps you should keep a few addresses for help with future columns.

—W. Robert Smith, Ph.D., Georgia State University

You are utterly incorrect about the game show question, and I hope this controversy will call some public attention to the serious national crisis in mathematical education. If you can admit your error, you will have contributed constructively towards the solution of a deplorable situation. How many irate mathematicians are needed to get you to change your mind?

—E. Ray Bobo, Ph.D., Georgetown University

You made a mistake, but look at the positive side. If all those Ph.D.’s were wrong, the country would be in some very serious trouble.

—Everett Harman, Ph.D., U.S. Army Research Institute

May I suggest that you obtain and refer to a standard textbook on probability before you try to answer a question of this type again?

—Charles Reid, Ph.D., University of Florida

You are the goat!

—Glenn Calkins, Western State College

# Goat Analysis

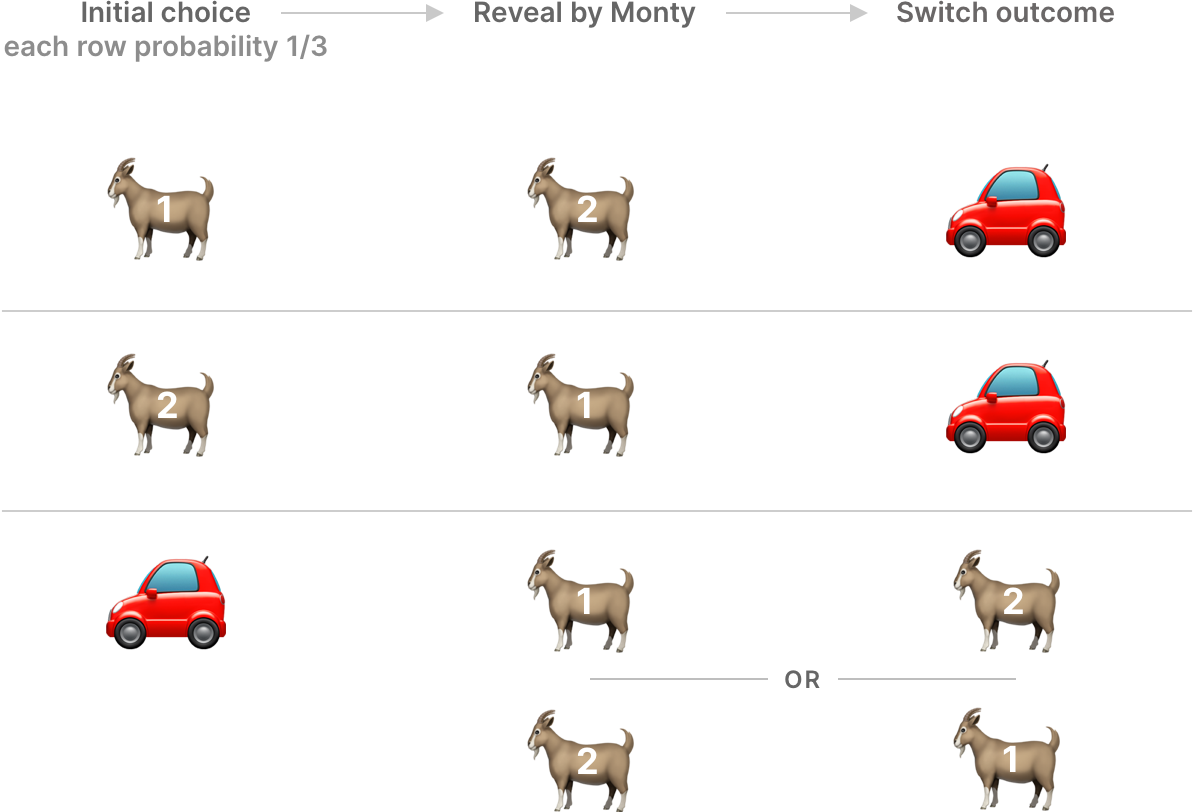

First, you pick a door, any door. Suppose you pick a door with a goat. Then Monty will show you the other goat, and you should switch to the third door. If you pick the door with the car, Monty shows you one of the goats and you shouldn’t switch. Since you don’t know what’s behind the door you initially selected, let’s follow Marylin’s logic of always switching.

If you happen to pick a door with a goat, then by switching you end up with the car. Two-thirds of the time you’ll be randomly choosing a door with a goat, so by switching you have a chance of getting the car. On the other hand, if you don’t switch, you’ll get your first choice (the first column) and wind up with the goat two out of three times. What Scott Smith, Ph.D., University of Florida gets wrong is that the chances are fixed after your initial selection. The host always shows you a goat and that doesn’t change the odds, it just changes which door you should choose next.

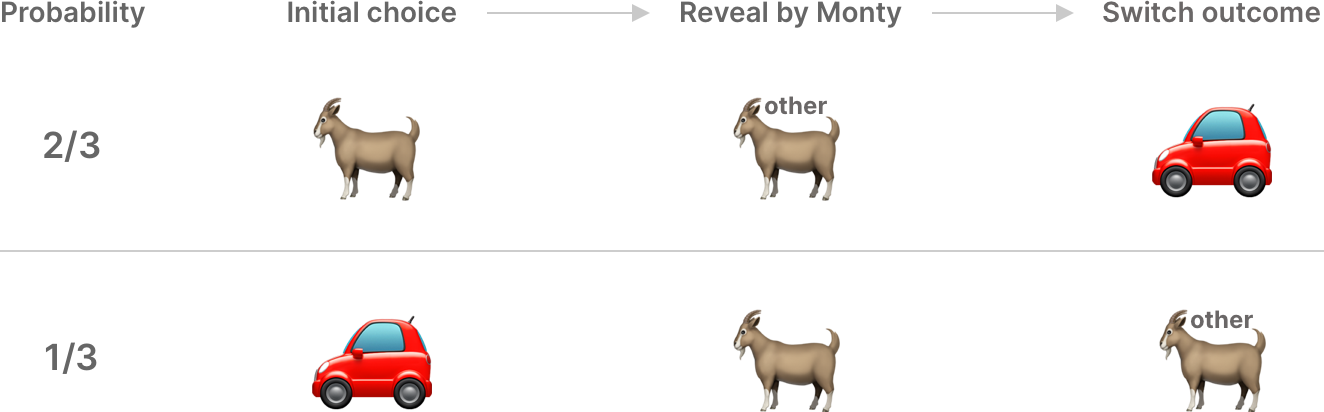

Maybe some people were confused by the last branch where you pick the door with the car and then there’s a split depending on which goat Monty chooses. Another way to look at it is that you’ll choose the top branch here with probability and the bottom branch with probability :

Could you improve your odds of winning the car by randomly choosing to switch or not? Suppose you decide to switch with probability . Then the odds of winning that shiny red car become

Since , the best you can do is set . In other words, always switch.

Years later, a reader asked Marylin if any of the irate mathematicians and statisticians had ever written back to apologize. She said,

Several of them wrote back, but none with an apology. Most maintained that the statement of the problem was ambiguous. However, plenty of other readers—people who had thought my answer was wrong but hadn’t written to say so and people whose letters weren’t published—wrote to say they had gotten it wrong at first but were delighted with the “aha” moment when they understood later.

There is one other possibility. Maybe you’re a farmer who doesn’t cotton to new-fangled contraptions and you’d actually prefer the goat. You probably don’t even have a TV or watch Let’s Make a Deal.

# Let’s Make a Simulation

You could start by playing an online simulation written by Adriano Garsia, a professor of mathematics at UCSD. His simulation shows that about of people who switched won the car. This is fun, but you don’t get much of a sense about the long term probabilities, and we can’t be certain that the code accurately reflects the game.

Another way to simulate the Monty Hall puzzle is with a pair of dice. You could let rolls of 1 or 2 represent door #1, 3 or 4 for door #2 and 5 or 6 for door #3. Let one die be the door with the car and the other be your initial choice. Notice that the only way you don’t win the car is when your initial choice is the door with the car. If the two doors are different, then by switching you get the car.

This is what I got after 52 rolls. There are 34 wins, meaning by switching I got the car 65% of the time.

| Car | Chosen | Win | Car | Chosen | Win | Car | Chosen | Win | Car | Chosen | Win |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 3 | FALSE | 3 | 1 | TRUE | 1 | 1 | FALSE |

| 3 | 1 | TRUE | 2 | 3 | TRUE | 3 | 3 | FALSE | 2 | 3 | TRUE |

| 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE |

| 1 | 1 | FALSE | 1 | 1 | FALSE | 1 | 3 | TRUE | 1 | 2 | TRUE |

| 2 | 2 | FALSE | 1 | 3 | TRUE | 2 | 1 | TRUE | 2 | 2 | FALSE |

| 3 | 3 | FALSE | 2 | 3 | TRUE | 1 | 2 | TRUE | 1 | 1 | FALSE |

| 3 | 1 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 1 | 1 | FALSE | 1 | 2 | TRUE |

| 3 | 1 | TRUE | 1 | 3 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 3 | FALSE |

| 3 | 2 | TRUE | 1 | 1 | FALSE | 2 | 3 | TRUE | 2 | 2 | FALSE |

| 3 | 3 | FALSE | 1 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 2 | TRUE |

| 1 | 3 | TRUE | 2 | 3 | TRUE | 1 | 3 | TRUE | 2 | 3 | TRUE |

| 2 | 2 | FALSE | 3 | 2 | TRUE | 3 | 3 | FALSE | 1 | 1 | FALSE |

| 3 | 1 | TRUE | 1 | 2 | TRUE | 1 | 2 | TRUE | 1 | 1 | FALSE |

# The R Language

For a much bigger simulation, you either need a lot of patience or to write some code. While this could be done in almost any language, this is a good opportunity to experiment with the R language. John Chambers, Rick Becker, and Allan Wilks developed a statistical language they called S while working at Bell Labs. R is derived from S and used by statisticians because of its many specialized statistical functions.

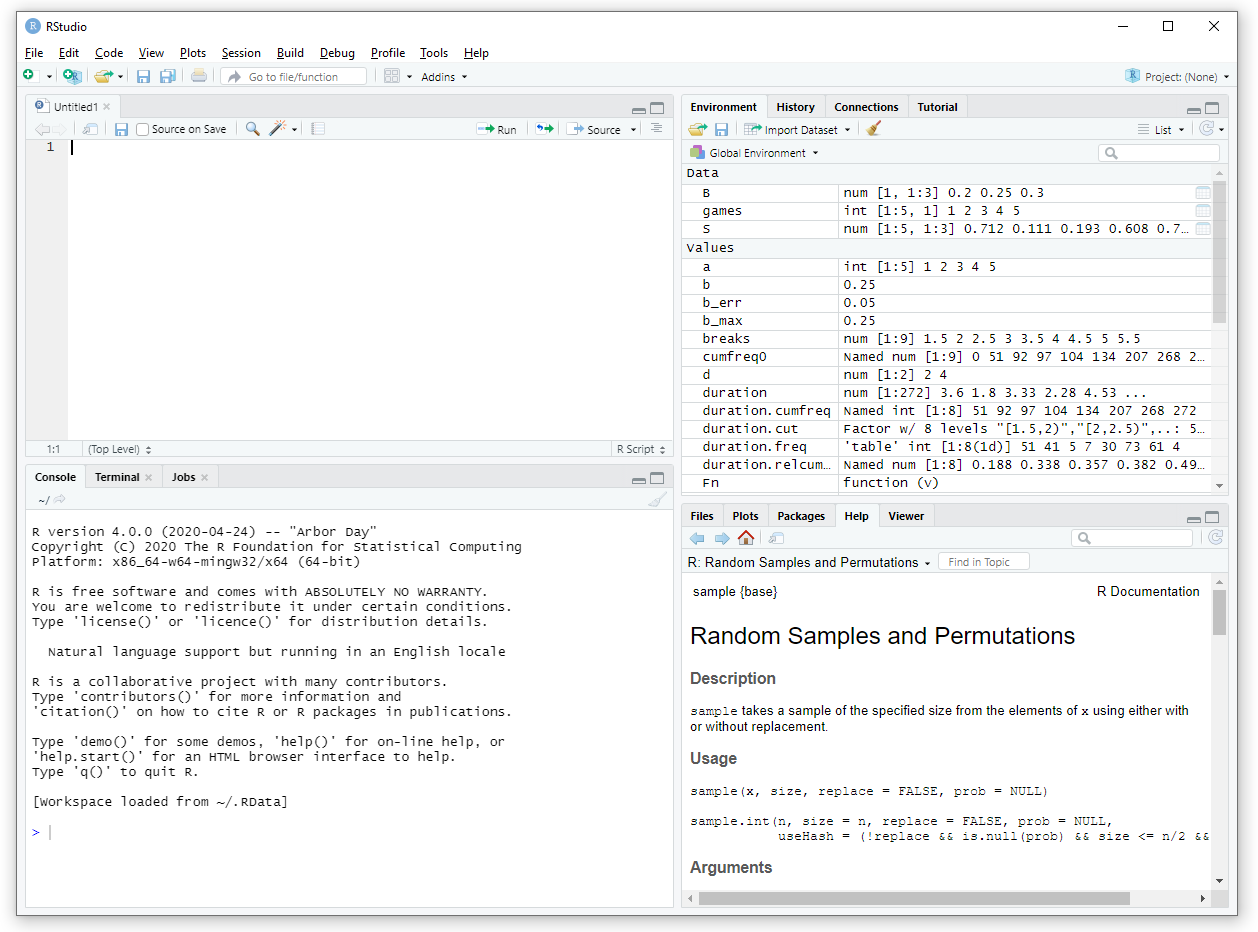

First, download and install R, and I recommend the IDE RStudio. RStudio provides tutorials for beginners to help get started with the environment, with the R language, and with associated packages. When you start RStudio, it should look something like this:

The upper left pane (click on the green circle with the white + below File if it’s not open), is where you can write new R scripts. The pane below is the console for interacting directly with the language. On the right side are panes for Environment, History, Connections, and Tutorials and below for Files, Plots, Packages, Help, and Viewer. You might find the RStudio Cheat Sheet handy, too.

The sample(x, size, replace) function in R is equivalent to rolling dice. The number of sides is set by x, the number of dice by size and setting replace = TRUE means that the dice are independent so a number appearing on the first die can also appear on the other die. For our experiment, we want 3 sides, and 2 dice, so the call should be sample(3, 2, replace = TRUE).

The program for simulating the Monty Hall problem is pretty simple. Initialize a wins counter, roll a pair of dice with the sample function n times, and if the numbers that come up are not equal, add to wins. Finally, divide the number of wins by the number of iterations to get the probability of winning.

montyhall <- function(n)

{

# Win counter

wins <- 0

# Loop over n samples, rolling a pair of dice

for(i in 1:n){

# Roll the dice

s <- sample(3,2,replace = TRUE)

# If the doors are different, win the car

if(s[1] != s[2]) wins = wins + 1

}

# Calculate the probability of winning

p <- wins/n

# Print the result

print(p)

} R uses <- as the assignment operator, so initializing wins to zero is done by wins <- 0. Rolling the dice puts a vector into s which you can see at the command line by

> s <- sample(3,2,replace = TRUE); print(s)

[1] 1 2and if the elements of s aren’t equal then wins is incremented by . The probability of winning the car is approximated by the ratio of the number of wins to the number of games played,

p <- wins/nAfter you’ve written the function, click the “Source” button in the upper right corner of the code pane. This will import the function into the command window and let you run experiments. This is what I got from one sample,

> montyhall(10000)

[1] 0.6626which is just about the expected.

Today’s pop quiz is the Mega Test. You have 15 minutes.